Exploring St. Louis

St. Louis has always occupied a peculiar lacuna in my personal history. It was the big city nearest to my hometown but was in long-term decline and lacked several attributes that Chicago had. Well over 90% of the time, if my parents wanted to do something in a big city, they steered the car north rather than southwest, up toward the Second City. St. Louis, only two hours away, had almost no resonance for me: the only images that I could conjure up were the Gateway Arch, some Cardinals games, my brother's residence for a few years. Later, I decided to rectify this oversight of my childhood and was able to stitch together a friend's private plane, Southwest, Greyhound, and Amtrak over a long weekend.

St. Louis has one of the most mysterious histories of decline of America's cities. Without having had riots like Detroit, Newark, or Washington, it emptied out at a pace that even its traumatized rivals could not match. In losing 61% of its population from 1950 to 2000, it allegedly experienced the greatest population loss of any city since Carthage, though surely some Nazi- or Soviet-occupied cities could have competed for this honor.

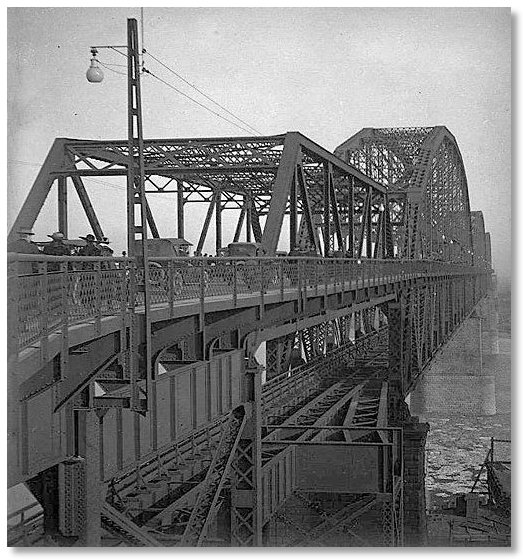

It has five car bridges across the Mississippi, but at times as few as two of them have been open, owing to amazing fecklessness by local authorities whenever a bridge has deteriorated. The steel-truss "Free Bridge" (see photo below), built in 1917 and renamed the General Douglas MacArthur Bridge in 1942, has been a railroad-only span since 1981, when part of the upper deck gave way. The current owner, a railroad consortium, has chopped off a segment of road at the eastern (Illinois) end to make the car ban permanent. From the riverbank, you can see the parallel 19th-century spans, all of which have the titanic and elegant Industrial Age ironwork that nobody builds anymore.

As soon as my Southwest flight landed, I picked up a transit day pass. Although America has nothing but contempt for those without cars, Rust Belt inner cities generally have tolerable transit serving their short distances. I rode light rail to Busch Stadium and headed south through deserted streets lined with old brick buildings until I reached Gratiot St., where a Ralston-Purina plant faced the blocked-off beginnings of the MacArthur Bridge. At the very start of the approach several MDOT trucks blocked access to a chain-link gate topped with a single strand of barbed wire. I went over it and kept going until I hit a second gate. You do not appreciate the dimensions of something engineered for cars unless you trudge, trudge, trudge uphill for several hundred yards and find yourself facing a second gate topped by three strands of barbed wire, still short of the river and a couple stories above street level. I-55, screaming with cars and the potential eyewitnesses inside, ran below. The pounding sun evoked the city's longtime reputation as major-league baseball's worst hellhole in the summer.

As soon as my Southwest flight landed, I picked up a transit day pass. Although America has nothing but contempt for those without cars, Rust Belt inner cities generally have tolerable transit serving their short distances. I rode light rail to Busch Stadium and headed south through deserted streets lined with old brick buildings until I reached Gratiot St., where a Ralston-Purina plant faced the blocked-off beginnings of the MacArthur Bridge. At the very start of the approach several MDOT trucks blocked access to a chain-link gate topped with a single strand of barbed wire. I went over it and kept going until I hit a second gate. You do not appreciate the dimensions of something engineered for cars unless you trudge, trudge, trudge uphill for several hundred yards and find yourself facing a second gate topped by three strands of barbed wire, still short of the river and a couple stories above street level. I-55, screaming with cars and the potential eyewitnesses inside, ran below. The pounding sun evoked the city's longtime reputation as major-league baseball's worst hellhole in the summer.

The humorless highway bastards had laced the ends of the gate with coils of razor wire to deter trespassers. Nevertheless, I figured that the chance of falling to my death going around the gate was somewhat smaller than the chance of being badly cut going over the gate, so I swung out above the city, treading on the razor wire and ferociously gripping the gatepost.