Camden the Damned

Not many tourists go sightseeing in Camden these days.

I did on New Year's Day, in pursuit of a public library that the city threw away in 1986.

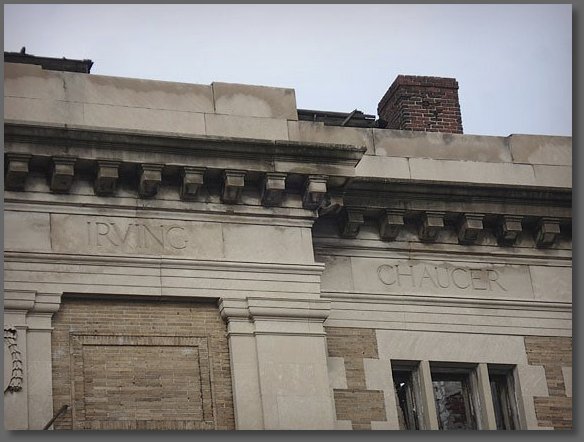

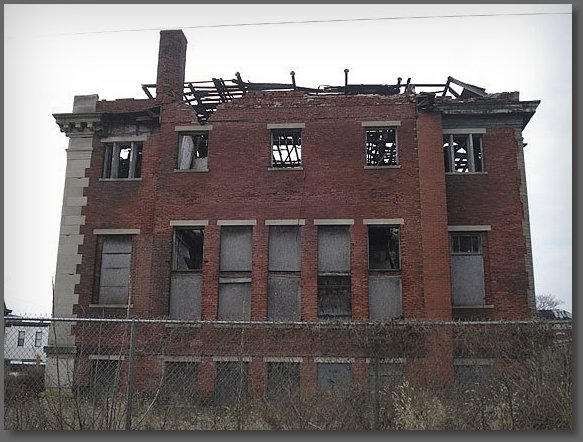

For years I had been haunted by photos of it that appeared in Camilo Jose Vergara's coffee-table book, "American Ruins." The picture of trees growing through holes in the roof stuck with me all these years when I lived even 3,000 miles away.

Finally, after too long a period on the hated east coast, I found time to journey up to Philly, which lies across the river from Camden.

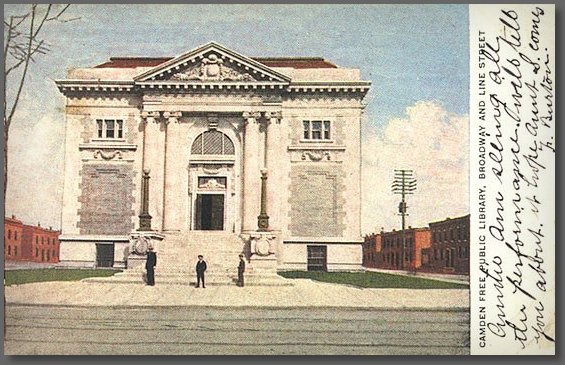

The old Camden Free Library, one of thousands funded by Andrew Carnegie, opened in 1905.

It witnessed decades of ups and downs, mostly downs, as the local economy died. After a human lifetime, the city fathers had enough of trying to keep up the building without having a tax base. They abandoned the library in 1986.

They did transfer the library to a larger building downtown, but the original sin of throwing away a Carnegie building remains. Today the old library is falling down beam by beam.

The first thing I did was to research the thriving city of the 1930s by borrowing the 1939 WPA guide to New Jersey.

It serves as a time capsule of attitudes and vocabulary of the 1930s as well as a portrait of prosperity that couldn't survive deindustrialization and race riots. Without any self-consciousness, the writers described the separate swimming pool and schools "for Negroes". "Negro teachers" taught there.

The guide describes the 22-story city hall and a sprawling Campbell Soup factory. It occupied 42 buildings over 8 blocks, including a model kitchen for visitors to admire. The plant folded in 1990, with the wrecking ball waiting.

The guidebook furthermore listed RCA Victor as "the world's largest producer of phonograph records." That particular factory sprawled over 10 acres with its various buildings before technological change made it and its work force useless.

Camden even had an airport before Philadelphia did, in those plummy days when Camden had 118,700 residents. It has 70,000 and falling now.

Now the bill just to modernize the sewer system and tear down the abandoned buildings would be an estimated $1 billion. Nobody has $1 billion to spare on fixing the poorest mid-sized city in the country.

Arriving in Philly on a sunny and cold New Year's Day morning, I found the PATCO line running under the river to Camden.

I got out downtown at the City Hall station and climbed blinking into another city center that had outlived its glory days, built of splendid masonry to last for generations. Those long-dead laborers surely never imagined their work would be left to crumble in place throughout the Rust Belt.

The 22-story city hall with its Depression-era friezes and inscriptions was still there, presiding over boarded-up buildings that could be measured in square miles.

The Campbell Soup site had become a parking lot for L3, the defense contractor that acquired the land.

One of the RCA structures, the one with a tower bearing 4 stained-glass images of the Nipper the dog listening to His Master's Voice, has become a luxury apartment building.

Others have disappeared or stand ruined, reminding one of Detroit.

After touring the tattered downtown, which included the first dedicated warming center I had seen (the lobby of a government building, where homeless can sleep on cold nights), I sought out the old library. It stands about six blocks south of downtown on 616 Broadway.

There would be no breaking and entering on this day. A barbed-wire fence surrounded the building, and eyewitnesses were thick on the ground. I settled for photographing it, as you can see below.

I ended my time in Camden by trudging southeast about 2 miles to Walt Whitman's grave. Back when he died in 1892, it was a thriving industrial town. Now he's buried in a slum. At least to the casual eye, his tomb doesn't seem to attract many visitors now. Things change; people forget.

I capped the trip by turning to that rarity of American life, a revived public transit line. NJ Transit's River Line runs on light rail between Camden and the state capital, Trenton. It began in 2004 after the original public transportation on that route ceased in 1963. Sooner or later, the asinine presumption that gasoline would be cheap and plentiful forever had to cease.

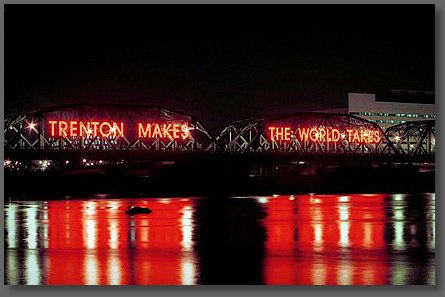

In Trenton, the River Line ends outside the SEPTA commuter rail station. I headed in and caught the $8 ride to Philly back across the river. The railroad trestle parallels a Delaware River bridge that still bears the sadly outdated sign TRENTON MAKES, THE WORLD TAKES.

(photo gleefully stolen off web)

That sign has hung there since 1911. Back then, the boast held true of factories and mills turning out "steel, rubber, wire rope, linoleum and ceramics," as a website honoring the bridge recalls.

Trenton spent 17 years (1985-2002) enjoying the distinction of being the only state capital without a hotel. The boast rings hollow now.