American Nomads

jan. 14, 1996

I lay shivering, watching the snow drift down, afraid to climb into my sleeping bag. It was a little past 11:00 pm on a cold December night. North Bank Fred, a veteran hobo, and I had found an open-sided shelter next to the railroad yard in Klamath Falls, Ore.

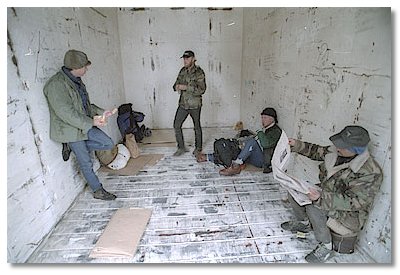

We were not alone. Across a small slab of concrete, five other hoboes sat talking around a lit Sterno can, passing among them a pipe of something that gave them obvious pleasure.

From the beginning, the talk was unnerving. Jonesy, who had been castigating his puppy for urinating on his bedroll, began complaining that his some-time girlfriend kept giving the dog a new name every week. First it was Tina, then it was Laverne, then Sally Louise.

"I hate those names," he complained. "They're too long. I want something short and easy. Why can't I just call her Bitch?"

At that point, another hobo's story was just concluding: "And then I found out he stole a six-pack from me, so I grabbed a board and I broke his leg for him."

This did not impress Cobra, his traveling companion, who began to brag about talking his way out of a second-degree murder charge in Arizona.

Such "tramp orations," as talks around hobo campfires are called, are notorious for their exaggeration. But the tales that night were vivid enough to keep me outside my sleeping bag, my hand clasped around my Swiss Army knife and in a position to defend myself.

I was on my second trip with North Bank Fred, and the romance of this hobo stuff was beginning to wear thin, a sentiment I didn't share with my train-hopping guide. Asleep a few yards away, his gray beard turned to the night sky, he was performing a nose ditty. He had an extensive repertoire.

Hoboes, tramps, train-hoppers - people like North Bank have been catching free rides on freight trains for more than 100 years. From Jack London to Jack Kerouac to Woody Guthrie, writers and singers have celebrated tramping as an American tradition. And, while the heyday of hoboing came during the Great Depression, when legions of the dispossessed rode the rails in search of jobs, train-hopping is still very much alive. It is also trespassing, and, thus, illegal.

Nobody is certain how many unauthorized freight riders there are today. Mike Furtney, a spokesman for South Pacific Rail Corp. in San Francisco, said that last year railroad agents recorded more than 30,000 "incidents" in which they kicked hoboes off SP's rail yards or freight trains. During that time, the railroad recorded 106 "trespasser injuries" and 57 deaths.

North Bank Fred (veteran hoboes often adopt monikers) is well aware of the dangers. The 48-year-old construction worker from Weed has ridden the rails for more than 20 years. He's been a rail fan since his father gave him a Lionel train catalog when he was 6. "I wore that catalog out reading it by flashlight under the covers at night," he said.

As he grew older, he matured into a tramp, traveling throughout the West and several times to the annual Hobo Convention that has been held each August in Britt, Iowa, since 1900.

"North Bank Fred is an expert and true connoisseur of train hopping," said Dan Leen, author of The Freight Hopper's Manual for North America: Hoboing in the 20th Century. "Riding is a central aspect of his life. He lives to hop."

North Bank, clearly a modern apostle of Huckleberry Finn, wouldn't disagree. "Some of my friends go skiing, some go hang-gliding. They don't do it because they are trying to benefit humanity or improve themselves," he said. "They do it because it's an adventure and it's fun."

For my first rail-hopping trip, I met North Bank at a motel in Dunsmuir. He had a half-empty bottle of his favorite rail-hopping beverage, Gallo White Port, in one hand. In the other, he held a computer printout listing all the SP trains moving through Northern California that night, a document he had talked out of a graveyard shift freight depot employee.

We were catching out of Dunsmuir, he said, because "the bulls here are mellow, there are no gangs, the air is clean and it's one of the best rides in the West."

At dawn, we were half a mile south of the station. Beside the tracks were several abandoned hobo campfires, wet from rain. Scattered between them lay a litter of cardboard, discarded packages of Top Cigarette tobacco wrappers, Darigold milk cartons, Taco Bell hot sauce packets and heaps of rusted iron whose original function was no longer discernable.

From out of a gully beside the Sacramento River trooped four hoboes and four dogs, out to see what we were up to.

James and Gypsy Lace were just passing through. He was originally from Chicago and had been riding the rails for more than 15 years, living off odd jobs and food stamps.

Gypsy Lace, a hobo for more than a decade, liked to winter in California but spent her summers in God's Love, a homeless shelter for railroad tramps in Helena.

They were guests of Lucas and his wife Eva, who had come out from New Hampshire five years ago. Lucas & Company - as he refers to himself, his wife and three dogs - are a fixture in Dunsmuir, where they have a shack near the river and live on Lucas' monthly supplemental security income check.

At least once a month, Lucas hops the freight to Klamath Falls to pick up his SSI check. But he's willing to pick up and go any time.

"Whenever that whistle goes, "Luke, Luke," I go riding," he said.

A long train from Roseville pulled in. North Bank selected an open boxcar and taught me how to get aboard. Standing to the left side of the open door, he reached up to grab a big latch handle on the side. Then, with a heave, he swung his legs up to the right and into the car. It's an elegant maneuver, much like vaulting a fence. I would later wish I had practiced it more.

We had hours to wait. We sat in the boxcar, whose rusted metal floor was covered with a patina of dirt, sawdust and rock salt, a mixture peppered with staples, nails, plastic strapping and small jagged pieces of sheet metal. The train, which was scheduled to leave at 7:30, did not depart until nearly noon.

"That's SP," shrugged North Bank. "Stands for slow and pathetic."

Lucas decided to join us as far as Klamath Falls, as did American Nomad, another hobo; he was headed north to find work on fishing boats in Alaska.

Finally, I heard a low rumbling. With a loud metal bang, the boxcar lurched forward, knocking me off my feet.

At first, we didn't go very fast - barely 30 miles per hour - but

the exhilaration that suddenly welled up surprised me. It wasn't just

the start of an adventure, or the evocative clatter of the train, or

the modest danger involved, or even the roguish thrill of stealing a

ride. It was all that and something unexplainable besides. Something a

dog with its head stuck out the window of a car would know.

At first, we didn't go very fast - barely 30 miles per hour - but

the exhilaration that suddenly welled up surprised me. It wasn't just

the start of an adventure, or the evocative clatter of the train, or

the modest danger involved, or even the roguish thrill of stealing a

ride. It was all that and something unexplainable besides. Something a

dog with its head stuck out the window of a car would know.

"Dunsmuir to Klamath is a killer trip," shouted North Bank, giving a thumbs up and trying to make himself heard above the din of the train. "Kick-ass views."

Out of Dunsmuir the train hugged the bank of the Sacramento River, pristine again four years after a devastating pesticide spill that raked it of life. Now fat fish fill its deep pools and numberless rivulets tumble down the steep, mossy canyon walls we passed so closely that I was able to run my fingers through the cascading water.

Later, as the train gained altitude and skirted the edges of cliffs, I saw a boxcar that had jumped the tracks and tumbled partway down the mountainside. Smashed and rusted, it lay suspended in a cluster of trees that kept its crumpled, rusting hulk from crashing into the valley below.

The cacophony of a rolling boxcar precluded conversation. Surrounded by 25 tons of loose-jointed metal, I was deafened by rattling doors, screeching wheels, banging couplings and an assortment of grinds, creaks, squeaks, booms and, most unsettling of all, the occasional loud ferric groan.

Without question, the second most important item in the train- hopper's kit is a set of earplugs to protect against this din. Cardboard is the first - a piece of cardboard is protection from a hard and dirty ride.

"Cardboard is revered by everyone who rides the rails," North Bank said. "It's often all there is between you and the elements." Well-muffled from the noise by earplugs and resting comfortably on cardboard settees, we lounged about the boxcar, watching the Northern California forests slide by. Then, opening on to the plains, we inhaled the scent of moist sage brought out by a recent light shower.

Soon it started getting cold, and when we stopped at one siding, North Bank and American Nomad jumped out and collected some wood. Inside the boxcar, they lit a small fire. They were careful not to build it over the wheels, where it might set off a sensor used to detect overheating brakes.

Huddled around our rolling campfire, American Nomad, who'd been across the nation many times, told of working 18-hour shifts on fishing boats in Alaska and discussed his loathing of homeless shelters, where he once caught scabies.

Lucas, North Bank Fred and American Nomad agreed the best ride for a hobo is a car carrier, those special trains loaded up with new cars. As high-priority freight, the trains travels at top speeds. All a hobo has to do is climb into one of the automobiles, turn on the ignition - for the key is inevitably on the dash - and blast across the countryside listening to the radio.

At dusk, we rolled into the large rail yard at Klamath Falls, passing a burning railroad tie that reeked of creosote, probably an abandoned campfire. Lucas and American Nomad hopped out and waved good-by. North Bank and I scouted for a train bound for Eugene.

Successful train-hopping requires that you follow a certain ballet of accommodation in a rail yard. If the bulls (railroad police) catch you, they will demand you leave the yard or arrest you. Engineers, brakemen and yard workers, however, feel it's not their job to nab hoboes. In Klamath, North Bank stopped a yard worker who was driving along a string of cars in a four-wheel scooter checking air brake connections. He didn't know the train's destination, so he called the tower and found out for us.

But while some employees may be friendly, a rail yard at night is a dangerous place. Trains can be surprisingly quiet, particularly when they are backing up. And at a hump yard (where cars are switched to other tracks by rolling them down a hill or hump) huge boxcars glide by silently and nearly invisible in the dark, imperiling the unwary.

North Bank and I soon found an empty boxcar on a train headed for Portland, a destination of personal significance. My grandfather, who lived in Milwaukie, a small town outside Portland, rode the rails as a young man, as did his father before him. Indeed, my great-grandfather lit out one day and rode the rails for more than a year and a half before returning to the family.

But we never made it to Portland. We had climbed aboard a boxcar that, once it got to full speed, shook violently because its wheels didn't track correctly. Thrashing about like a rogue shopping cart with wobbly wheels, a "rocker" bounces its occupants around like popcorn off a hot pan.

Standing is dicey because you are forever stumbling about trying to get a grip on something. Lying down is preferable, but sleep is out of the question. You bounce along the floor of the boxcar, while your head does a rhythmic slapping against whatever you're using for a pillow.

Sitting cross-legged with my arms braced against the floor, I spent seven hours one cold November night composing angry letters in my head, each more furious than the last, excoriating the president of the Southern Pacific Railroad for his damnably rickety trains. That I was an uninvited, not to say illegal, guest did not lessen the severity of my opprobrium.

We arrived in Eugene sometime after midnight, and for the next two hours we roamed the rail yard, skirting the big vapor lamps, searching for a return ride. Stumbling in the dark over ties, twisting our ankles on ballast (the rocks that form the rail bed) we skulked about constantly on the lookout for bulls, the railroad agents whose job is to thwart train-hoppers and trespassers like us.

This is North Bank's idea of fun.

In the dark, we examined three trains, each with up to 100 cars, but every boxcar was locked or packed tight with freight. So, seeking a place to sleep, we checked the dry ground beneath an overpass, but three youths had staked a claim. We unrolled our bags next to a ditch and slept. It began to rain at 3:00 a.m.

The next morning, we found a boxcar on a southbound train. The door already had been spiked (jammed open with a railroad spike by other hoboes). Few circumstances are as frightening as having a boxcar door suddenly slam shut on you. They are impossible to open from the inside (even from the outside, the railroad uses a forklift to open them) and you can be trapped for days.

We passed the morning watching the rain drain off the roof of the boxcar and picking through the remainder of our food. I had packed only cheese, flat bread and kippers, imagining, wrongly as it turned out, that opposite every rail yard stood a small, picturesque cafe, where I could have flapjacks and eggs.

The hobo population can be divided into three classes. The largest is migrant workers, who cross the border and follow the harvest, picking lettuce in the Imperial Valley, grapes in Napa, berries in Oregon and apples in Washington.

Then there are so-called stamp collectors: homeless men and women who collect SSI, or who register for food stamps in several cities along a train route - Eugene, Roseville, Oakland. They ride the circuit, triple dipping on the government's largesse.

Finally, there are rec riders, train lovers such as North Bank Fred who ride the rails for recreation. For them, riding is a venerable pastime and an occasional adventure.

After riding the rails for 24 hours, I was cold, wet and fed up with the stench of the boxcar and tired of the hunger, of swabbing out the last bit of oil from a kipper tin with my dirty finger. I asked North Bank, "Why do you do this?"

He looked at me. "You mean when we could be sitting back in a cozy living room drinking beer and watching the game on TV?" he asked.

"Yeah," I said.

"And, you mean, beside the fact that it's a cheap way to travel, you get to see all sorts of stuff and it's a generally groovy thing to do?" he asked.

"Yeah," I replied, "beside that."

He thought a moment. "Sometimes I think that in a weird way it's about achieving privacy. You leave your home, your job, the town you work in, the people you know. And you ride alone. When you meet people, you don't use your real name and you don't ask personal questions. You're anonymous and completely dependent on yourself."

The train pulled out of Eugene about 1:00 p.m., headed southeast over the Cascade Range back to Klamath and Dunsmuir. For hours we rode past the rain-swollen Willamette and up into the mountains, passing under snow sheds and through countless tunnels - rattling around in the dark for more than a minute before emerging on the other side.

Suddenly, North Bank grabbed my arm, pointed to the boxcar door and shouted something. He looked alarmed and I fumbled to get my earplugs out.

"The door is closing," he shouted. Sure enough, spiked or not, the big metal door had moved. What had been a six-foot opening was now a three-foot gap. "There's an open boxcar four cars down the line," he said. "When we stop at the next siding, we've got to change cars."

I was hoping we could discuss the matter further because it was approaching dusk and we were nearing the summit of the Cascades, 40 miles from nowhere.

Twenty minutes later, the train slowed to a stop in the snow at the summit. Now there was only an 18-inch opening at the door. We squeezed our packs out, then hurried back to the boxcar North Bank had seen, but it was closed. My stomach dipped, but North Bank spotted another boxcar further down the line and broke into a trot.

Halfway there, I heard the ominous hiss of air brakes, then a clank, and I began running as fast as I could. I got to the boxcar first, just as it began to move. My hands scrambled around for the latch beside the door, but it wasn't there - nothing to grab on to. I walked along the now-moving train, stumbling on the ballast, trying to think what to do.

"Jump," shouted North Bank, behind me.

I put my hands on the floor of the boxcar and tried to boost myself in, but my hands slipped on the wet metal.

"Jump," yelled North Bank, as the train moved faster. Again I tried to boost my way up and into the boxcar. I got about halfway in, struggling against the counterweight of my pack, when suddenly my legs flew up and over my head and I tumbled inside.

Running along the track, North Bank had flipped me in. As the train picked up speed, he grabbed the edge of the door frame and swung himself up and into the boxcar.

I picked myself up, stuck out my hand and said, thanks. "Nothing to it," said North Bank, who pulled out the White Port, which we finished right then.

That night, the weather cleared somewhat and I spent hours watching the dark silhouettes of trees flow by while the quarter moon, as the poet said, like a dying lady, lean and pale, sank below the horizon.

I slept well that night, rocked, this time gently, in the cradle of that big boxcar. At 6:00 the next morning we had arrived back at Dunsmuir, where we'd started. We trudged through a gray mist verging on rain the length of the train to the depot.

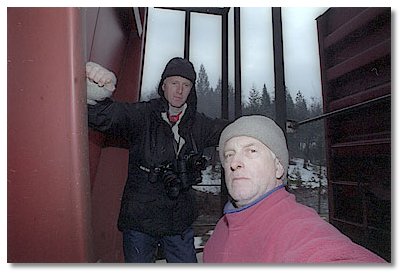

I never thought I'd go train hopping again. But a month later, I was back with North Bank in Dunsmuir, this time in the snow. Maybe I was trying to get in touch with my past, with the experiences of my grandfather and his father before him. Or perhaps it was a desire to hop back on that rolling parallel universe, a world not available to ordinary folk. Certainly it had a lot to do with creosote fires, stumbling through dark rail yards and shooting through the Cascade gaps.

But I can't really explain it. Let's just say it's a Huck Finn thing, and leave it at that.

Though it is a venerable tradition practiced for generations, hopping freight trains is both dangerous and illegal. Technically, train-hopping is trespassing and those caught can be arrested and jailed, though spending time behind bars for hoboing is rare.

Last year Southern Pacific Rail Corp. alone tallied 106 "trespasser injuries" and 57 deaths on its property. Many, though not all of these accidents involved hoboes or train-hoppers.

In addition to accidents, train-hoppers recently have been beaten or killed in California by a roving gang of thugs who go under the name of the Freight Train Riders of America (FTRA).

In his 25 years hopping freights, North Bank Fred has been injured several times and was once cut by a rock that came flying into a box car. William Mellman, who has started a train-hopping home page on the World Wide Web, was hit by a bird as he was riding a freight going about 50 miles an hour. It took more than 20 stitches to sew up the cut along his eye and the side of his face.

Riding freight trains may seem like an archaic pastime, but there's nothing old-fashioned about the way some of today's train-hoppers communicate. When they aren't catching trains, they're hitching rides on the information superhighway.

The World Wide Web, the graphic interface for the Internet, has at

least four web sites devoted to train-hopping, and several newsgroups

are devoted to the subject as well.

The World Wide Web, the graphic interface for the Internet, has at

least four web sites devoted to train-hopping, and several newsgroups

are devoted to the subject as well.

In fact, I got a quick seminar on train-hopping by typing the word "hobo" in Yahoo's Internet directory, and later, via the Internet, found someone willing to act as a guide.

The computer-literate hoboes populating cyberspace generally are not those who hop trains out of economic necessity. Rather, they are so-called rec (recreation) riders, who travel freight trains for adventure and have become immersed in the freight-hopping subculture.

"It's anyone who loves to ride freights," said Bill Mellman, an Indiana resident who created his own home page. Some are computer geeks, others are students - including one University of California at Santa Cruz Ph.D. candidate doing an anthropological dissertation on hoboing. Most are simply rail fans who also have access to computers.

Mellman's home page (ezinfo.ucs.indiana.edu/~mellman/trains-netscape.html) is a prominent site on the Web. Mellman includes a series of frequently asked questions, maps, film recommendations and stories from other train hoppers. Most importantly, he offers a warning/disclaimer page in which he stresses the danger of the activity.

Another common hobo stop on the Web is The Train Hoppers Space (www.catalog.com/hop/). This colorful site is devoted to both novice and veteran hoppers. Wannabe tramps can get an introduction to train-hopping, browse an extensive book list, learn what supplies to take with them and find out where to catch trains. The more experienced can read, or even submit, their own tales of the rails, pore over rail maps or link to other sites.

But the best of the Internet isn't on the Web but rather on the several newsgroups devoted to hopping. Here rail enthusiasts and hoppers swap information, regale each other with freight-hopping yarns and thrash out controversies.

The biggest disagreement is about publicity. Most rec riders are eager to share their adventures, as well as train-hopping tips, with other initiates. But many fear wider publicity in the print or broadcast media. Some are concerned that wider coverage will encourage kids to engage in an activity that is not only dangerous but illegal. Others don't want to draw attention to the pastime for fear rail authorities will crack down on train-hoppers.

Among the messages that flew through cyberspace when I posted a message saying I wanted to write a story on train-hopping: "I suspect this alleged reporter is just another bozo trying to get a quick story credit about something he/she has no chance of doing justice to." Another suggested that it was "very dangerous to expose it (train-hopping) as being romantic fun and adventuresome, as well as very easy." A third opined: "Frankly, I don't trust reporters any further than I can throw them..."

Dan Leen, author of The Freight Hopper's Manual for North America: Hoboing in the 20th Century, doesn't share the concern over publicity.

"My approach is that people should have access to information," he said. "Sure, you must stress that it's dangerous, but if you stopped writing about things because they were dangerous, this would be a very dull world."

Airedale - Someone who travels alone rather than with other

tramps.

Bindlestif - Hobo (stiff) with a bedroll (bindle).

Bull - Special agent in a railroad yard charged with security

and with catching hoboes.

Catch out - Hop on a freight train.

Gondola - Short-sided, open-topped car used to hold scrap or

garbage.

Gumboat - Gallon-sized can used for cooking.

Home guard - Local tramps who don't ride.

Hopper - Covered grain car; also called a grainer.

Hopping - Riding the rails.

Hot train - Train with a high priority, usually heavily loaded

with goods going to market. Other trains must often pull over at

sidings to allow hot trains to pass.

Hot yard - Rail yard actively patrolled by unfriendly

bulls.

Hump - Low hill in a switching yard used for sorting cars by

gravity.

In the hole - Waiting at a rail siding, usually for a train

with higher priority to pass.

Jungle - Hobo's camp site.

Mission stiff - Tramp who stays in a mission or homeless

shelter most of the year.

Pig train - A piggyback train, one composed of flatcars

carrying truck trailers.

Roll out - To bed down for the night - by rolling out one's

blanket or sleeping bag.

Stamp collectors - Tramps who travel from town to town

collecting food stamps along a circuit.

Streamlining - Traveling without a pack, extra gear or

bedroll.

Surfing - Riding on the tops of rail cars while they are moving

(a good way to get killed. Rarely done by veteran tramps unless they

must get to another car).

Sources: North Bank Fred, Hobo Times and Chronicle research