The Salt of the Earth (part 2)

is the spice of life

Trudging into the deserted freightyard through 6" of wet snow, I tried to psych myself up by remembering those miserable 98° days in the Summer and searching for shade at every opportunity. It's a good thing I wasn't searching for shade today because there was none — just a low overcast with a nasty wind and no empty cars in the yard for shelter.

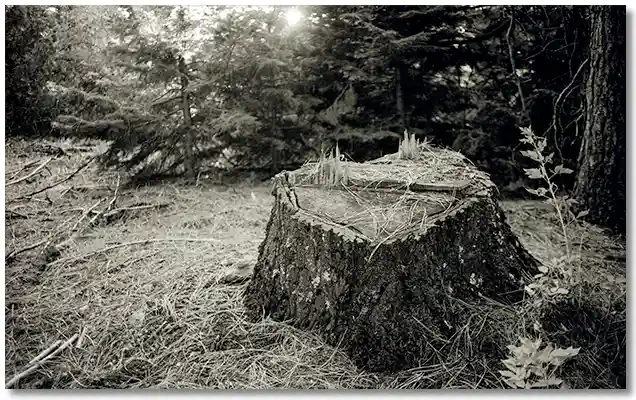

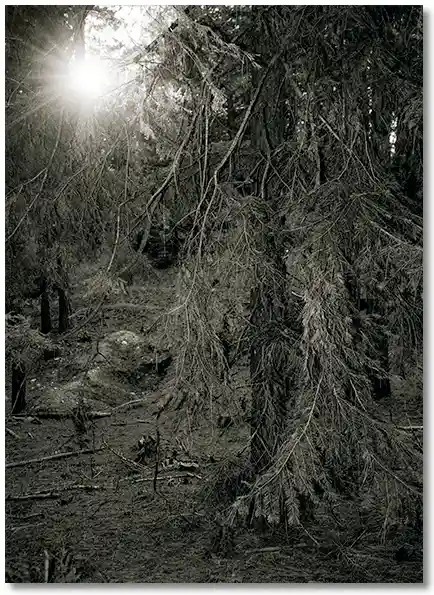

Heading into the woods to look for a spot to wait, I was relieved to see that under the canopy of Ponderosa Pines there were patches of bare ground, and this is where I unrolled my cardboard and set up "camp" to wait for a northbound. The only drawback was that I couldn't see the signals on the mainline, which meant I would have to develop a keen interest in distant train whistles.

Bringing out all of my food to prepare a feast would surely bring a train (as it often seemed to), but I resisted the urge and uncapped a bottle of White Port instead. This did wonders to help me forget about the cold and wind, and the wait became more enjoyable as the day wore on. Between sips, I laid out my gloves, scanner, and flashlight, as what little daylight was here to begin with was quickly fading away. As soon as I heard a whistle I could pack up my stuff in a minute and be ready to go... all I needed was a whistle.

Drifting off to sleep sitting up, I was released from a dream of freezing somewhere in the snow by the whistle (actually the horn) of an approaching northbound. As planned, the gear was stowed and I walked over to the edge of the trees to scan the incoming train. The first 20 cars or so were closed boxcars, but then an empty showed up, and then several more, so after the head end passed by I began to work my way over to the mainline as the train slowed to a stop.

A brakeman on the other side of the train was spinning a handbrake shut, and then the front end of the train pulled forward, leaving me to casually inspect the empty boxcars. The first one looked good — doors open on both sides and reasonably clean. I checked the latching pawl to make sure that they wouldn't slide back and forth when the train was moving, then moved back a few cars to look at the next empty, which was nearly identical to the first. Seeing that the engines were lined up to an adjacent track to set out some cars, I knew I had plenty of time and continued my walk down the train looking for suitable rides.

A couple more boxcars came into view — no better or worse than the ones I already passed, but then I came upon an old wooden-floored car with both doors open and a pleasant surprise inside. Apparently whatever was shipped in this car previously must have been sensitive to damage, as there were several huge pieces of cardboard stapled to the splintery wooden walls to provide a smoother surface, and a couple of big chunks of oak timbers that looked like they had been nailed to the floor to keep the load (whatever it was) from moving. I hopped inside to get a closer look and realized that the cardboard sheets could be torn down to make a smooth, clean floor and the oak chunks could be stacked up to create a chair!

Leaving my pack in the doorway, I hopped off to inspect the doors and check the wheels for flat spots. Everything looked good so I climbed back inside and began to do a little housekeeping. The cardboard was re-arranged, the wood stacked, and I settled into my "throne" to survey the domain spread in front of me. Shortly the engines re-connected to the train, the air was pumped up, and we slowly pulled down the siding, where we suddenly came to an abrupt stop. Turning on my scanner, I heard the Dispatcher tell my train to tie it down, as there was a broken rail somewhere ahead and they'd be there for awhile.

Usually when the railroad uses the term "awhile" it ends up relating to Geologic time, and seeing the snowfall begin again, I stood up to walk around the car and figure out my next move. If we sat here for several hours I would end up going over the Cascades at night, and miss out on the most scenic part of the trip. About the same time as I was ruminating over this thought I looked out the door and saw a thin wisp of campfire smoke rising above the manzanita brush across the mainline from my boxcar. Knowing that I had plenty of time for exploring the surrounding area, I closed up my pack and hopped down, looking for a path through the brush that would get me closer to the mysterious campfire. A few minutes later I almost stumbled literally down into a large pit in the middle of the manzanita, where a smoldering fire poked out of an old cast iron utility sink that had been sunk into the ground. There were a few chairs and a table, but no sign of anyone or their gear.

The source of the fire was a large chunk of a railroad tie, and it looked like it had been burning for quite a while. There were no cooking utensils around to indicate that someone was actually "using" this camp, just a lingering fire, which I stoked up with a handful of more or less dry pine needles. Dropping my pack and settling into one of the rickety chairs, I brought out a bottle of White Port and decided that I would let Fate decide if I was to go or stay.

In an ill-named location called Rattlesnake Canyon I saw what still remains the best tramp hooch I've ever seen. On the Washington side of the railroad bridge just west of Wishram is a canyon that goes up into the rimrock overlooking the Columbia River Gorge. At the bottom of this canyon, a little ways off the mainline of the Burlington Northern railroad, sat an extraordinary example of hobo ingenuity. I forgot the name of the tramp who lived there, but he had barbering skills and would give haircuts to those in need. His hooch was amost the size of a boxcar in square footage, but only about 6' high. I wasn't sure what was used for framing, but the outside walls were plywood, with the roof being held in place by numerous large rocks piled here and there. A short picket fence surrounded the place, and when I first walked up the occupant was busy sweeping the walkway into the house using a railroad switch broom.

The practice at that time was for trains that were crossing from Washington down into Oregon to stop at the wye on the north end of the bridge to line the switch for their direction of travel. That meant every southbound train, whether from Vancouver or Pasco, would have to stop before crossing the bridge, and this made for an easy place to get on, and was the reason I was waiting here. Taking a break from his sweeping, the tramp waved me over and I set down my pack and made his acquaintance. We chatted for an hour or more before he excused himself for his mandatory afternoon nap, and I walked over to the river bank and found a nice rock to sit back on and enjoy a bottle of Ernest & Julio's finest.

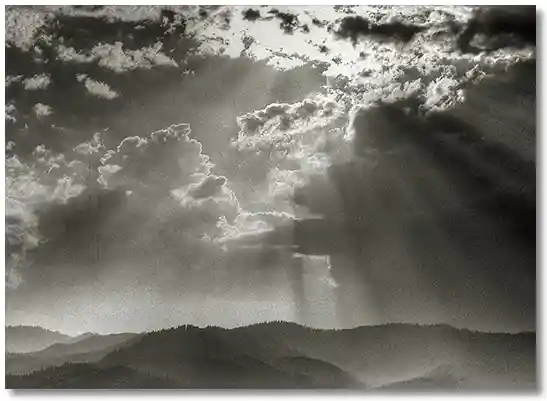

Sitting on my rock, I could see the occasional barge traffic on the river moving from my right to my left, or from my left to my right. At the same time, there would be cars or trucks going the same way on the Interstate on the Oregon side, as well as Union Pacific freight trains on the adjacent track. As these horizontal migrations were unfolding before me, and as I worked my way down the wine, I wondered if there ever was an imbalance in the population between the West Coast and the East Coast. Was there an identical number of cars, trucks, barges, and trains in either place, or did their populations fluctuate, like ocean tides?

The deeper I got into the wine, the closer I came to sliding off my rock into the river, but not before I was able to add data to my observations. I started keeping track of birds that would fly either to my right or left, then some puffy clouds that defied logic and moved only to my left all afternoon. Looking down at the water below me I wished that I could see which direction fish were swimming, to add to my knowledge database. Fortunately, as my head began to swell with an information overload, a train approached from the west and stopped at the wye. Gathering up my gear and walking over to the south leg of the wye I saw that the switch was lined out the east leg, so my train would have to stop again, giving me plenty of time to find a ride. In a few minutes we moved across the bridge onto the Oregon side and I was now merely another data point moving east...

Riding the Northwestern Pacific was a favorite pastime when I lived in Sonoma County. A northbound train left Petaluma during the day and went to Geyserville, about 30 miles north, where the southbound train met it and the crews swapped trains. It stopped here and there along the way to work, but there were always empty boxcars going north, and it was a fun way to go for a ride without having to drive very far. If the northbound train got to Geyserville first, which it almost always did, there was time to walk a block up from the tracks where there was a nice café to hang out while we waited for the southbound.

There were crossing gates where the road to the café crossed the tracks, and being only a block away, if we leaned back from the bar and looked out the door we could see the gates when they came down, signalling that the southbound train was ready to leave. By paying for our beers ahead of time, as soon as we saw the gates light up and drop down we'd bolt for the door and run down the street to the tracks, where it was easy to get on as the southbound pulled by at a walking pace. I don't remember ever getting an inside ride on the way back, but after several beers we didn't mind riding outside. One time, however, after getting off early at Healdsburg, there were no rides other than closed boxcars on the southbound, but fortunately there was one boxcar with the ladders running all the way up to the roof, so we climbed up and rode the 20 or so miles back to Petaluma stretched out on the roof of the car. We realized that we weren't doing a very good job of hiding when we went by several grade crossings in Santa Rosa and heard car horns honking and people waving. While it did seem to be an "interesting" way to travel I'm sure that none of us did it again.